Every single person on the planet has a story. We never even walk by the vast majority of them. Then there are those we walk by without seeing; the ones with whom we have brief encounters without really listening; those who share our lives in some way but whose hearts we rarely see into; and, if we’re very fortunate, a few with whom we exchange intimate confidences.

There’s an interesting phenomenon, a side effect of traveling, that involves the instant and inexplicably deep personal connection between people who meet, share a few hours or days, and never meet again.

A special bond is perhaps forged as a result of similar cluelessness about surroundings & cultural behaviors, or lack of routine and familiar faces. Or maybe the freedom of absolutely zero preconceived notions or previous acquaintance. Tabula rasa.

There was the family from Latvia who shared a lodge with us in the Peruvian Amazon. She confided that they’d been having marital problems & were moving to Boston where her husband had been offered a professorial position. Maybe a change of place would improve their relationship. They were traveling with their children for a year before the new academic year. He was determined to go to a shaman in the jungle to experiment with a special hallucinegen and unpleasant about her reluctance to join him. In the end, they left their young children and their passports with us – people they’d known for two days – and headed into the jungle.

In the morning they still hadn’t returned. Thankfully, they straggled back a little before noon. Hungover but healthy in body if not in mind.

And so it goes. We tell each other things we haven’t told close friends. We trust each other with confidences, money, and apparently sometimes our children. We enthusiastically join in adventures we might have had trepidations about. We listen to, tell, and enjoy vastly different opinions, occupational stories and familial foibles unselfish-consciously. We laugh a lot.

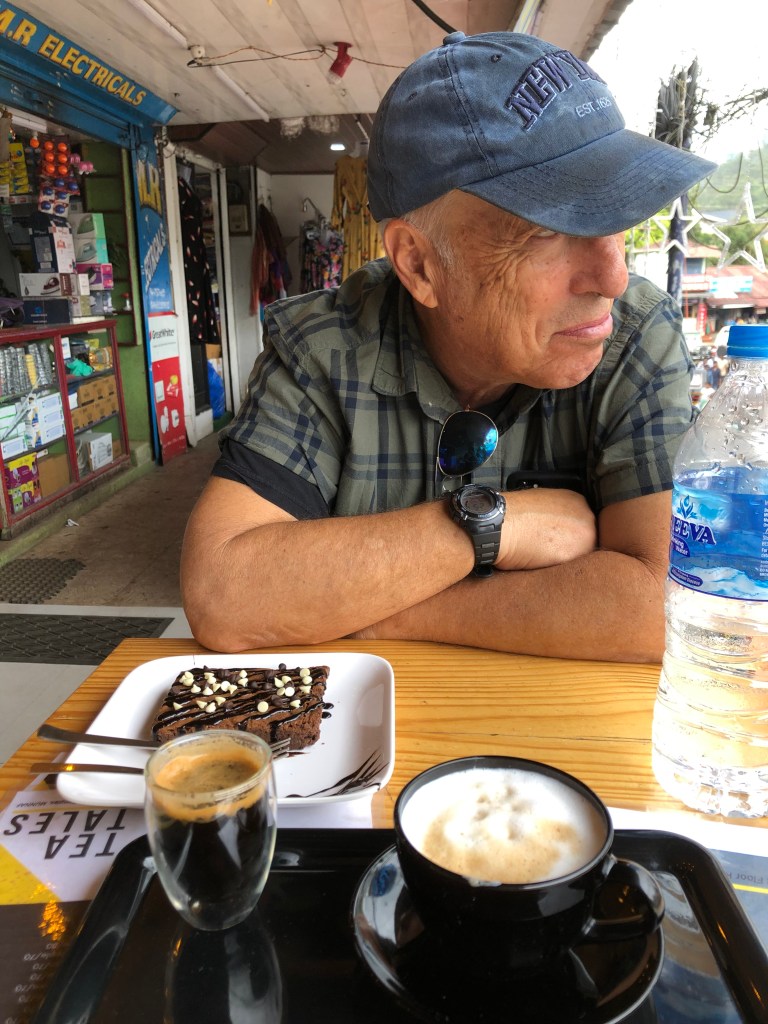

Antony (no ‘h’ in the many Antonys in Kerala, even St. Antony, and if you see an ‘h’, it’s not pronounced. There is no ‘th’ diphthong there.) was born in a very small fishing village in Kerala. Son of a fisherman, Antony loves nothing more than being out on the water in a small boat, meeting with childhood friends, hearing the waves lap the shore or crash on the rock barrier near his home. He chose a different life, though. Antony went to the military academy and spent 24 years in the military, retiring from his last position as Colonel, in charge of the anti-terrorist unit in northern India. He’s a hero in his hometown, and elsewhere. He went on to establish three businesses in the area surrounding his fishing village, employing over 90 people. It keeps him busy and away from his fishing village and the sound of The Arabian Sea. He’s not particularly interested in money for himself. His wife, Teresa, manages their bank accounts, saving what’s needed for their two children’s university educations, and gives Antony a small monthly sum to fill his motorcycle with gas and buy coffee during the day. He established businesses because he recognizes that along with employment comes dignity for his friends and neighbors. He’s also one of fifteen men who meet monthly to play games, share stories, and put money into the kitty for anyone who might be in need. His home is open to people at every level of society and they are happy to join him there for a drink or just a visit. Antony decided long ago that at sixty he’ll retire, he’s 49 now, and give himself the gift of The Arabian Sea’s whisper in his ear every day. An eclectic man, he never ceased to catch our interest or raise thought-provoking questions for discussion – philosophical as well as ‘what if’s’. We felt honored to be invited to his nearby home for dinner with his wife and son (his daughter was away at preparatory exams). It’s clear how much his son admires him and what a loving father he is (he told us that his wife keeps the kids in line because he can’t tell them ‘no’). I’m sure he was a tough officer in the military – he’d have to be – but in civilian life he has mischief and the sparkle of laughter in his eyes and a huge heart filled with kindness.

Katie’s only daughter lives in Pondicherry. Katie wasn’t much of a Mom. She was a flight attendant for Air France for her entire professional life, flying here and there and rarely at home. Her ex-husband raised their daughter. Retired now, she spends several months a year in Pondicherry, resigned to never being able to make up for lost time with her daughter, but determined to be a part of her life. A passionate woman, Katie’s views about French politics control a large part of her life. In the streets every weekend in her yellow vest, her harsh political rhetoric intrudes in almost every conversation. Macron, and Sarkozy before him, are the devil incarnate. And, yes, she does use those words. Enemies of the people, proponents of a new world order that disenfranchises everyone but the wealthy, robbers of the private benefits and income of the middle classes and the poor. Her political anger seeps into her extreme watchfulness in order to protect her from being taken advantage of, even by our sweet, accommodating host in Thekkady. We invited her to join us for a quiet day of walking in nature, surrounded by cardamom, coffee, and tea plants. Calmed by the sheer serenity of all that green, her political persuasions faded into the background, only occasionally peeking out to make a brief appearance.

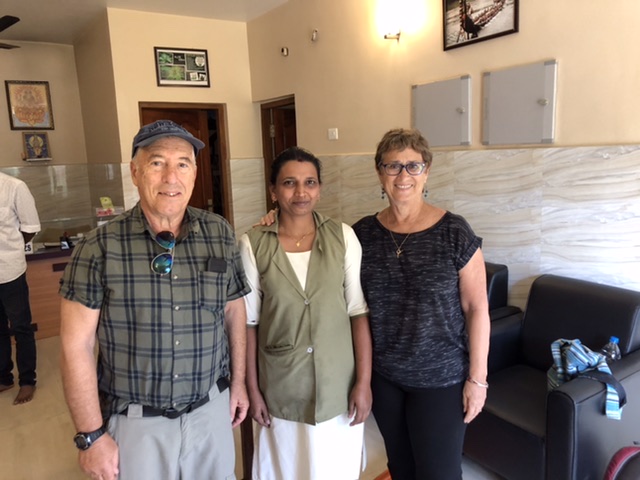

Nancee was born and raised in a house in the forest, 40 kilometers southeast of the Kerala city of Munnar. She lives there still, in her house surrounded by fruit trees and passion fruit vines, and walks the kilometer to work as cook and cleaner in a three-story guesthouse/hotel owned and run by J.P. A quiet, shy woman, her smile can light up a room. When we commented on how much we loved the passion fruit that showed up on our breakfast table after we requested fresh fruit, she brought us a bag of the most delicious passion fruit I’ve ever eaten. I come from a country known for its plentiful, extraordinary fruit – picked in the morning and in the market in the afternoon. Passion fruit is one of my favorite fruits, but I’d never seen passion fruit so big, firm and tasty. She’d picked them from the vines surrounding her home, along with large cocoa pods (interesting, but not so tasty). She acquiesced graciously to my request to watch her cook our breakfast so that I would be able to replicate it at home, only a little embarrassed at first to have me looking over her shoulder. When we left, after two weeks at Arusakthi Riverdale, she approached me hesitantly, hugged me fiercely, then joined her palms at her heart and gave me a small bow. We didn’t understand each other’s verbal language but the language of our hearts was loud and clear.

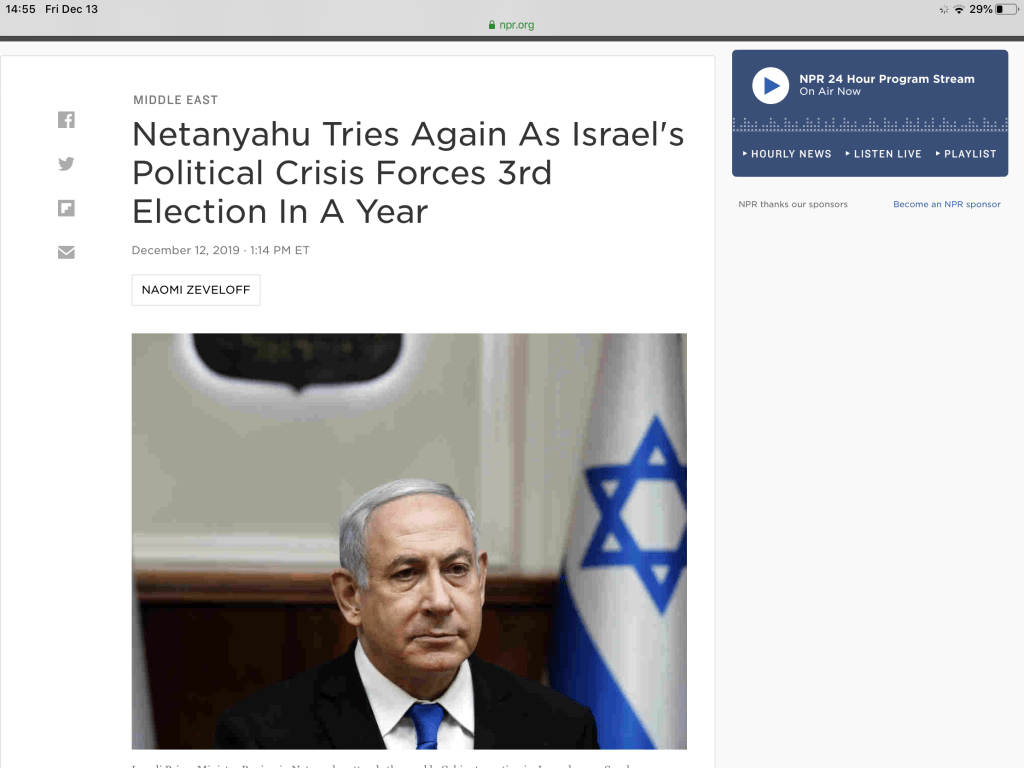

Rav Yonaton wears a mixture of Indian and Hasidic clothing, along with his long payot (side curls) and large kippah (skullcap). Born and raised in London, the son of a totally secular family, he moved to Israel where he became religious, married, fathered a son, divorced, re-married, lived joyously in poverty, and shared in learning Torah with his new South African wife. Waking up to the necessity of providing for their upcoming baby, he lucked into a job as a mashkiach (kashrut supervisor) for a Baltimore company and relocated to Jewtown, India, near Fort Kochi (Kochin). His wife joined him there with their month old daughter two weeks later. Ever enthusiastic, ever sensitive to the cultural and social realities around him, Rav Yonaton has endeared himself to the largely Catholic community. A nice mural of him walking with his daughter can be seen on the wall of one of the newer, more comfortable hotels. The Hindu family across from a memorial headstone for a Kabbalist from the 17th century, located in an alleyway, helps to make sure the memorial’s burning light never goes out and joins the Rav there sometimes when he comes to daven (pray) there. We looked forward to having a bit of chicken after over a month as vegetarians, but there were only small bits of fish in the rice for Shabbat. Rav Yonaton explained to us later that he prefers to respect the poverty of his neighbors and not stand out as having the more expensive chicken on his Shabbat table. His contract will expire in the fall and he has no idea if he will be returning to unemployment, but his infectious smile precludes worry about his family’s future. As he walks us back to our hotel after havdala (the prayer to end Shabbat) at his house, he greets and is greeted by most of the passersby, each in his own language (and there are many). Loving and loved, he has no worries.

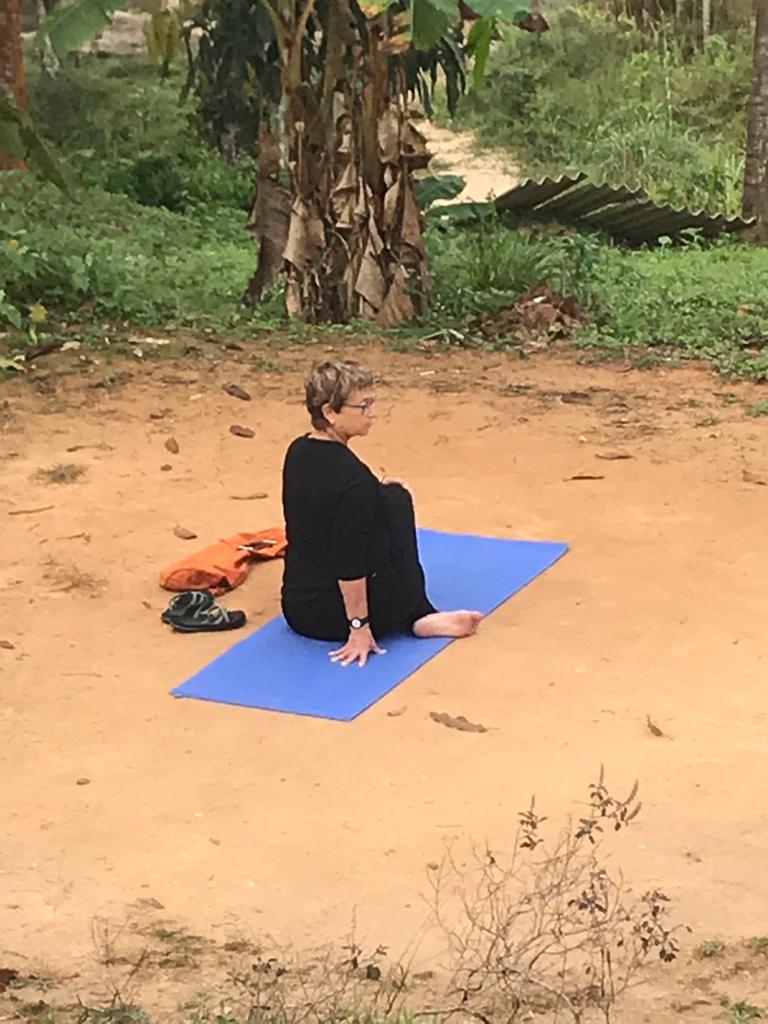

Vita and Ben are getting married in June after sharing their lives for over seven years. They’ve moved to Stamhope Hill in London, where she is a researcher for an NGO whose task is to evaluate the work of other NGOs and he is a youth worker in an adventure camp. They clearly both love their work and each other. She never wanted to marry and, in fact, when he proposed for the umpteenth time while on a romantic vacation in Japan (and was confident that she’d say ‘yes’), she told him to ‘Fxxk off!’ After a 20-minute conversation about why he wanted to marry, she was convinced, demanded he re-enact his proposal and afterwards said ‘yes’. He’s into the whole large wedding in a spectacular venue thing and she’s going along with only minor irritation in her voice as she reacts to his telling us the plan. Why marry at this point? Children are definitely on the horizon. They share a beer or two with my partner as laughter gets more and more raucous. Vita and I bond more over morning yoga on the balcony overlooking a tropical jungle. Our own temporary piece of paradise. We all swap hiking stories from beautiful Periyar National Park. They’re younger than our youngest child but age differences disappear easily among travel buddies.

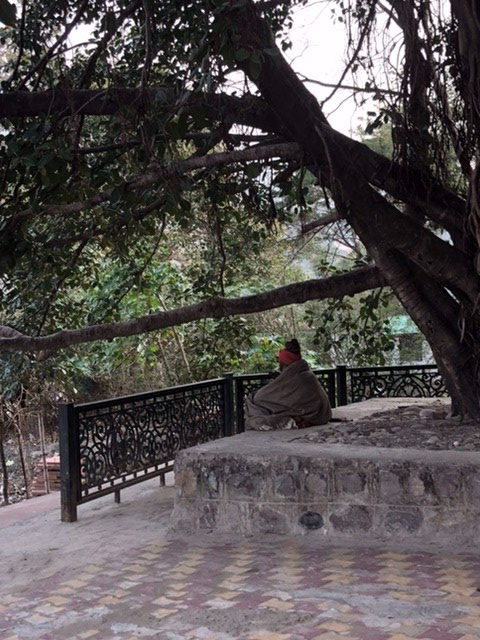

Viktor is a solo traveler from Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. Somewhere in his late 40’s or early 50’s, he shares in the lives of his nephews but doesn’t see children in his future. A businessman, he’s not exactly rich but wealthy enough to help his extended family wage a decade-long (losing) battle for his ancestral home against the municipality, and pick up and come to a meditation seminar after an online Sadh Guru meditation course. Because of jet lag, he overslept and arrived two hours late to the seminar where he was turned away – ‘The Guru gave explicit instructions that no late arrivals were to be admitted.’ Offered an alternative – a 3-day retreat at the Sadhu Guru’s ashram in Coimbotore – he decided to attend and extend his time in India. That’s how we got the opportunity to make his acquaintance in Morjim Beach, Goa. We learned a lot about Armenia – he’s a super patriot. His only regret about living in Yerevan is that no one there is into spiritual meditation, or at least he hasn’t found anyone. He and my partner talked together for hours about Armenian history and politics. We visited the local fish market together and chose a big fish to have our cook fix for us one night. The cook didn’t like the look of the one we picked out so carefully, jumped on his motorcycle with it, returned it to the fish market, where he purchased a better fish for us. It was totally scrumptious and we shared a wonderful evening together with the sound of the waves and a lot of shared stories. Having fallen in love with Goa (What’s not to love? Beautiful, empty, clean sand beaches and gorgeous sunsets.), he extended his time there and we bid him adieu before heading for Kerala.

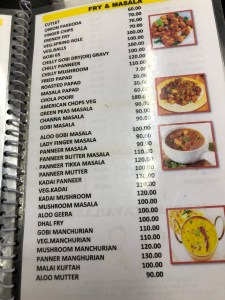

Ruth and Dieter, an Austrian couple, joined us for several days in Thekkady. We have a love of pure veg South Indian food in common that made walking down the potholed road outside our guesthouse together to The Hotel Aryas a given. They are as adventurous as we are when it comes to experimenting with new dishes and more so when it comes to eating with their hands. They went on a 20 km hike in Periyar National Park the day my partner went on a 15 km hike and I read for a couple of hours before meandering the streets and shops of Thekkady happily NOT hiking for hours and hours. They were to leave for a tree house hotel close to Ayursakthi Riverdale the next day but when they heard our praise for our amazing guide, Raj, on our 5 km nature hike earlier in the week, Dieter, a botanist finishing up his PhD, couldn’t leave without joining us on a return engagement with Raj. It meant they had to spend an extra 2500 rupee (about $40) to hire a taxi to get to their next town because they’d miss their bus, but they were game. We were happy to share the experience with them. Raj didn’t disappoint and it was so much fun watching how excited Dieter was to learn all about the flora in Periyar. Raj knows the common name and scientific name for every flower, tree and bush. Ruth, an occupational therapist, has amassed tons of botany from her many years with Dieter, as I have gained knowledge of bugs and crustaceans from my years with my partner. It was a pleasure spending time with such a like-minded couple, in spite of their being Austrian, barely thirty years old, and being in India for the first time.

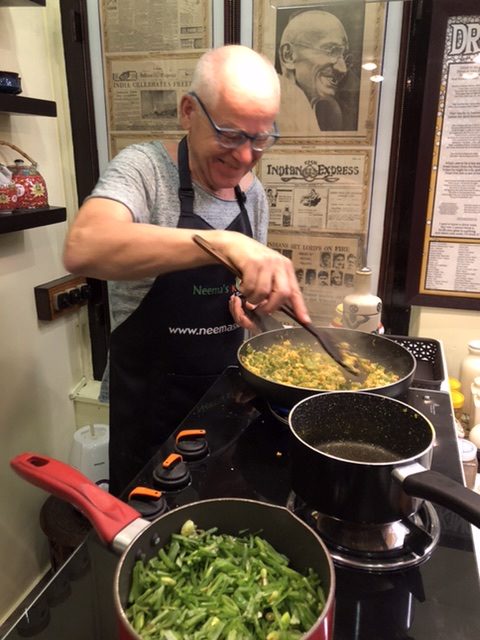

Neema taught me to cook South Indian dishes, including the masala dosa my partner loves so much. More importantly, she and her husband, Prasad, spoke to us for many pleasant hours about their India, their family, and their experience working with many tourists. A soft-spoken, gentle soul, Prasad actually worked for many years as the captain of a commercial line of ships. Neema spent her first five years of marriage (an arranged marriage, of course) traveling along with him, visiting ports all over the world, even after their daughter, Olivia, was born. It was a special privilege only the captain’s wife enjoyed. Once Olivia was a bit older, they settled down in Neema’s parents’ historical landmark home in Wypeen Island, just a short ferry ride away from Fort Kochi (Kochin). Neema’s parents live in the house as well, though we never caught sight of them. Prasad is well-read, andknowledgeable in many areas including history, Indian and world politics, world geography, ichthyology, a bit of botany, and many languages. As Neema taught me to cook, Prasad and my partner kept each other entertained. Prasad was the one to open up the, formerly unknown to us, history of Jews further north in Kerala. After cooking class, Neema put her feet up and we chatted about being mothers of independent, strong-minded young women, building a business which relies heavily on customer service, the trials & tribulations of developing and maintaining a social media presence, remembering to give back to the community, and, of course, where to shop for clothes and gifts close by for good prices and quality.

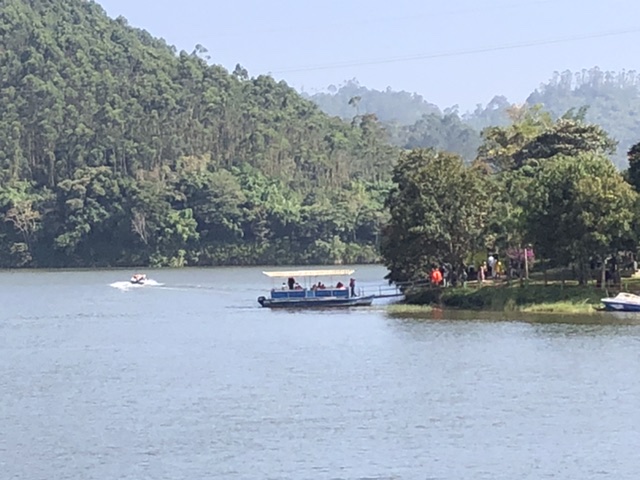

Raj Kumar is a member of the indigenous mountain tribe called the Munnan. To this day they live in small villages in the mountains with a king and village elders. When outsiders approach one of the villages, an elder meets them outside the borders of the village to decide whether or not to allow them to enter. The Munnan have control over Periyar National Park, though it’s technically a government park. The Munnan have always had control, considering it their tribal land. Of the the 357 square mile park only 118 square miles are accessible to tourists, in order to properly conserve the fauna and flora. As a result, elephant herds live in their natural age-old way, goddesses of their territory, are infrequently sighted, and make it clear with threatening noises and agitated behavior that they should never be approached from less than 100-150 meters. The park rangers are all Munnan. They guide small groups on nature hikes from 5-18 kilometers and carry out night patrols to be sure that poachers cannot harm the animals or protected flora, including sandalwood and mahogany trees. Raj Kumar was randomly selected to guide us on a 5 km hike. As we waited for a British couple, Peter and Sara, to join us, their hotel agent having asked if we agreed to add them to our private hike, Raj began to describe the park to us. We were immediately impressed by his knowledge, English, and ability to field queries. As we watched him pull the raft to shore for us to cross the small lake, he suddenly dropped the rope, patted me on the shoulder and said, excitedly, ‘Come! Come!’ He took off up a small hill and we took off after him. Once we hit the peak, our eyes followed his pointing hand across the water where a mama elephant and her baby were grazing. A beautiful sight that his sharp ears, hearing the older elephant cooing to the younger, made possible. We were to learn to trust his ears, eyes and instincts, which directed us to the huge Malabar Squirrel, two glorious Hornbill birds (who took off in flight and flew overhead, exhibiting their full colors and shapes), beautiful butterflies of many different colors, caterpillars of all sizes and monkeys high up in the branches (before they began throwing things at us). There was not a common name or scientific name of any flower, bush, or tree that he didn’t know and recite easily. He was happy to allow us to sit silently, without moving, for five minutes, at my partner’s request, in order to hear the increased sounds of forest birdsong and the noises of animals in the trees once their wariness disappears – a moving experience to try if you never have – but hold out for 20 minutes! My partner, a water biologist and ecologist with a PhD, and Raj, an autodidactic naturalist, found kindred souls in each other, swapping facts and vignettes from nature. Raj proudly told us, neither modestly nor arrogantly, that, though it was commonly believed that the jackal lived in Periyar, it had never been proven until he took a photo, at his own peril, after stalking a jackal for many hours. We arranged a second hike with him two days later and, had we stayed, would have been happy to go out with him a third and fourth time. There just seems to be no limit to the changes in the forest from day to day or to his understanding of nature’s glory.

Only a third of the way into our 6 month trip in India, I could add many more travel buddies to this already-too-lengthy post:

Abdul, our host, our twins’ age, who graciously took us on the worst road we’ve been on in India so we could have the day we wanted walking through quiet fields, unharrassed by tour guides or crowds, and was nonplussed when something important fell down from under his car after one particularly deep hole in the road. He found a piece of cardboard in the trunk and a tshirt and tied the cardboard under the car before happily climbing back into the driver’s seat and taking off. He explained one morning, with a chagrined smile, that his guesthouse, motorcycle, and junky car all belong to the bank – loans he hopes to pay off someday. A familiar cross-cultural story.

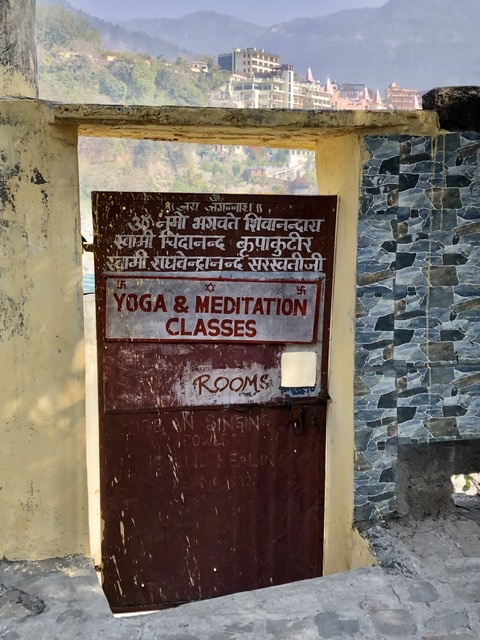

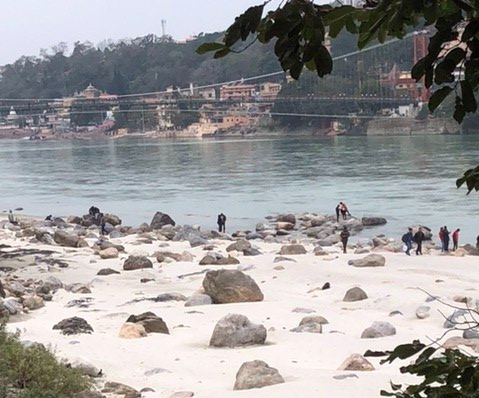

J.P., another host, perplexed that most days we just hung around the river behind the guesthouse or took the 8 km walk across the bridge, circling back through the small village. He never stopped asking eagerly if we wanted a tuk-tuk to go into Munnar each morning (we went 3 times during our two weeks there). He loved that he and I share a daily yoga practice and smiled with a small bow each time I came back in, though his own daily practice was long over (he does a half hour at 5 a.m.). When we left he gave us a brightly colored red and gold something or other (??) and said we would always be family. He’s since sent Whatsapp messages asking how our trip’s going and then wishing us a happy 2020.

Kavarappa maintains an art gallery on the third floor of his home on a sleepy residential road in Mysore. We found the Bharani Art Gallery online, hired a tuk-tuk to take us there, found the gate locked and no one around. Our driver called the number we found online and Kavarappa opened the gate and then the gallery for us. Some of the art was fascinating. My partner is contemplating buying a piece of Vedic art by a Finnish painter. Kavarappa then invited us into his home for coffee. The conversation was great and quite informative. He is Coorgi (Coorg is about 130 km from Mysore) and still has a coffee and pepper plantation there which, sadly, his two children will not take over from him. The way of things in India today.

The list goes on, but this post doesn’t.

One common denominator of travel buddy relationships is the desire of human beings to be really seen by other human beings. And it may be that reason that relationships are telescoped while traveling – because of their necessarily ephemeral nature.

The very sweet young waiter, who served us dinner for 13 nights, spoke almost no English but summed it up far better than I can explain it when he said shyly, as we departed the rooftop restaurant for the last time,

“Please remember me.”