Our youngest son, Rafael, moved with his family to New Jersey last night. We don’t know how long they’ll be there. We don’t know why they moved.

Neither of their excellent jobs requires the move. They have a beautiful house here that they renovated just 5 years ago to their exact specification. Their garden is flourishing, as are their kids. All four kids have many friends and are happy here. They have an active social life with friends and with their siblings/cousins. The other grandparents live a 15-minute walk away, are retired, and are always happy to have the kids over, pick them up, and take them places.

The given reason is that they get itchy when they’re in one place too long. They seek adventure (in New Jersey? 😂) They seek a challenge when things are too settled and smooth. Our son fears getting stodgy (he’s 42). At 40, having made partner at the most prestigious law firm here, he quit to do something else. He didn’t want to get stuck in a rut.

I sort of get it. I was that way myself. But once we had kids, I reframed my need for change into something more compatible with having first one and then, within 7 years, five kids. I changed professions six times; just about every 2 or 3 years. I wrote a few books. Once the kids were a bit older we traveled…a lot.

And, of course, the biggie – we moved from the US to Israel.

Rafael and his family moved to the US once already. They spent 5 years in Silicone Valley. He’s a hi-tech lawyer so that made sense. It provided him with the lift he needed to become one of the younger partners in his law firm. We missed him. The 10-hour time difference and 16-hour flight were brutal. But it made sense. And once was enough.

This move makes less sense to us.

Of course, we’re ten years older.

My in-laws were devastated when we moved our own young family to Israel. My mother-in-law literally keened and wailed when we parted at the airport. But, we felt, we were moving toward something. It was an ideological move. It was living our dedication to Zionism. We still feel that way.

What kind of ideology could possibly warrant a move to New Jersey – the state Americans love to mock? Clearly (to us) they are moving away from something and not toward something.

I get that, too. Living in Israel is not for the faint of heart.

Although it has one of the strongest, most stable economies in the world, wages are relatively low, real estate is ridiculously priced out of most young families’ reach, and many families struggle to get through the month. None of this applies to Rafael, who is blessed with financial stability.

Israel has been at war from the moment the state was established in 1948. Sometimes the war is more volatile and sometimes less, but it’s a constant threat. Our neighbors make no bones about hating us and have consistently made clear their goal of destroying our state and killing us all. The past two years, since the atrocities of October 7th, have been traumatic for every single family in Israel, and continue to be so.

Hard times, however, seem to strengthen Israelis’ resolve, not weaken it.

The divisiveness in Israeli society over politics and religion seems to be more of a factor in people leaving Israel than the war. The exaggerations and fears on each side lead to a lack of tolerance that feeds on itself.

For those of us who left comfortable lives in the US (or other Western countries) to live in Israel, we take a dim view of those who leave. It would be more accurate to say that many of us look upon it as betrayal of an ideal; betrayal of the country. In addition, given the current ugly anti-Semitism in the world, we believe that Jews should be aware today more than ever that Israel is the place for Jews to live.

We worry about our children and grandchildren’s safety. We worry about our grandchildren being taken out of a place where they are like most everybody else – it’s not an issue – and put in a place where they are ‘the other’.

We believe that our son and daughter-in-law have a tremendous amount of talent and skills to give to our country, and that our country needs people exactly like them.

And, perhaps most of all, I’ll miss being able to drive an hour whenever the spirit moves me and enjoy a good cup of coffee and great conversation with my youngest son. He’s the best! I’ll miss all the many special things about each and every one of those four delicious children. And, yes, sometimes, of course, I feel that strong twinge of sadness and loss in my heart.

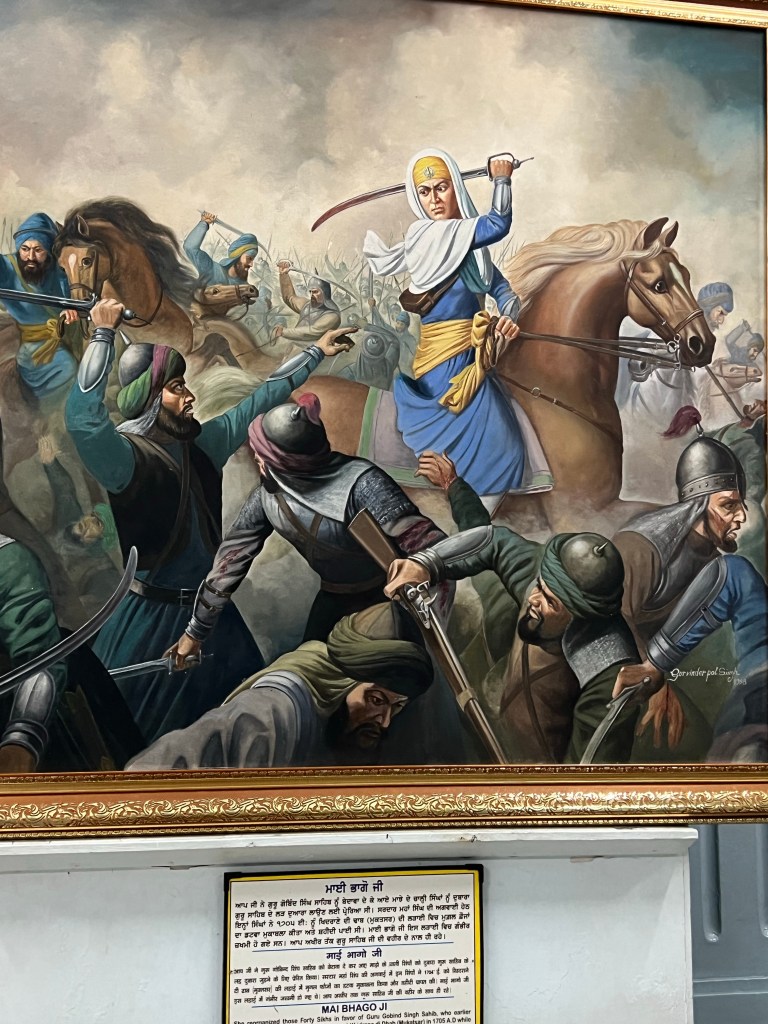

Tisha B’Av is the day that our first two holy temples were destroyed. The date is commemorated with a 25-hour fast and special prayers. When tragedy strikes and someone is very sad we might say she has on her Tisha B’Av face.

That’s the face I see on many of our friends lately when considering our son’s departure with his beautiful family.

And, ironically enough, I want to console them.

“But nobody died! They’re only going to New Jersey!”

As hard as it is for us to imagine, they’re off on what they see as an adventure for their family. We made our choices. Some of them were great and some not so great, but they were ours to make. And if they turned out to be not so great, we readjusted and reframed and began a new adventure. Or at least I hope you all did, because we sure did. Why be stuck when life is so fleeting?

I, personally, believe they’ll be back in a couple of years. After all…New Jersey. And in the meantime, how fortunate that in this day and age there’s Facetime and WhatsApp and convenient flights.

They’re a happy, successful, healthy couple with four amazing, funny, quirky, interesting, healthy kids. We’ve had them near us for five blessed years and, G-d willing, we’ll have them near us again one of these days.

So chin up, friends, no Tisha B’Av faces, please.