I was reading a book by one of my favorite authors the other day (Table for Two by Amor Towles). In a bit of a digression, where some of the best of his extraordinarily expressive language lives, he took me back over 50 years to my first encounters with my husband. When I say he took me back, I mean in that instant I felt a flash of pure joy all through my body. It wasn’t just a memory of thought. It was a full body experience of the senses.

I saw him sitting with one blue-jeaned leg dangling, the other under his butt, leaning forward, crossed arms resting on his thighs. His hair was dark and long – a little under his chin all over. He was wearing a dark green, long sleeve t-shirt. His eyes were sparkling – sorry if that sounds kitsch but I don’t know how else to convey the feeling that his eyes conveyed.

I imagine the immense talent of an author to create such an event in his reader makes it all worth it.

It was a flash. No more than 5 seconds. But it started me on a journey.

My husband and I have been together for over 50 years. We thought we were all grown up, adults, when we met. We’d both been living on our own for several years. He was 23 and I was 21. Kids. It was the early 70s. We’d come of age in the 60s with all that entails: the music, the drugs, the irreverence, the belief that we could change the world.

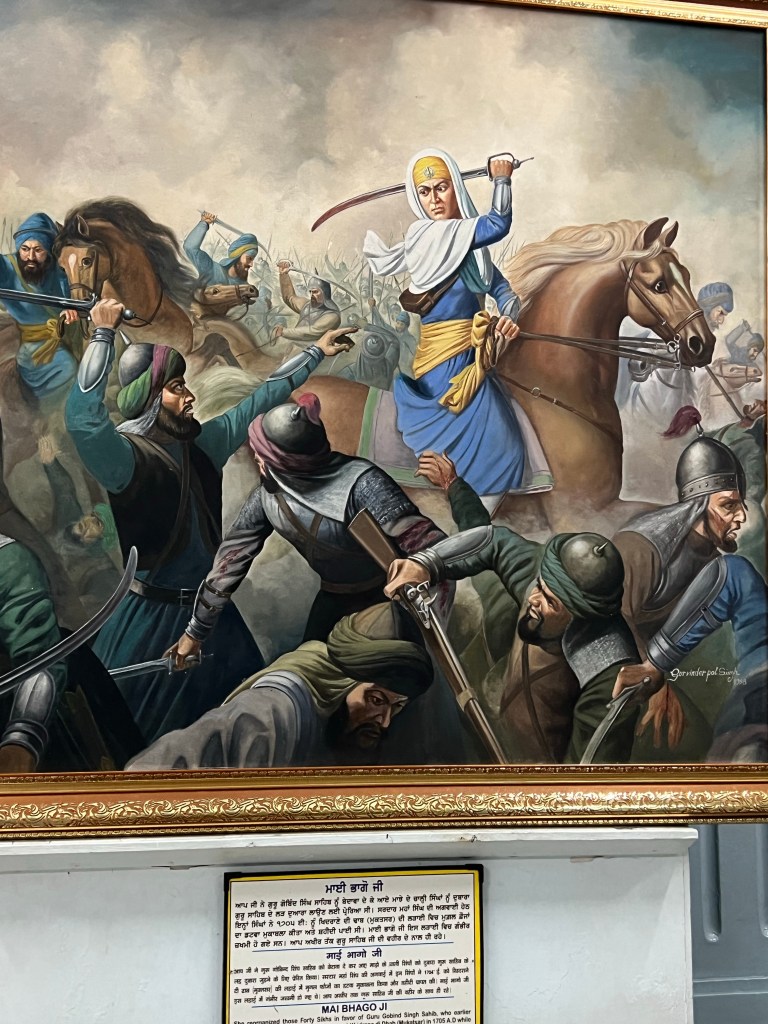

He was the political activist: co-founder of the very first Earth Day, member of SDS (until their anti-Israel stance, an anathema to him even in those days), arrested at anti-Vietnam war demonstrations. I was the flower child, grooving to The Jefferson Airplane and Country Joe and the Fish on the grass in Golden Gate Park, selling candles at Woodstock.

We fell in love over bowls of chili at Rennebom’s Drug Store, 6 foot tall photographs of Galapagos turtles, street parties, and listening to Nixon resign the presidency where we sat in a small bar in Texarkana and the big-haired bartender cried.

We were first stunned to find out we were going to be parents and then confident that we would be able to do it all. Finish graduate school, feed and house the three of us, and continue to change the world

I had the confidence and sense of adventure to be immediately excited at the prospect of what our love had produced (how hard could it be?) and he had the concern about how we were actually going to make it work to keep us grounded. From food stamps, to married student housing, to a cooperative day care solution, our two natures combined to see him through his Masters degree, and nourish a beautiful, sweet natured little girl who constantly charmed us both.

From digging our car out of the snow to get to a pharmacy during a miscarriage scare, to meandering with my best friend, our first daughter, through the arboretum, to the shock of looking at the primitive ultrasound of our twin babies two years later we lived the roller coaster together.

As anyone who’s been lucky or blessed or stubborn enough to persevere and arrive at the point where a marriage can be labeled a Long Term Relationship knows, it’s not always smooth sailing. Plenty of drama, tears, and crises. And it doesn’t always seem worth it. Raising five children with no financial support, not having experience a good example of parenting, and doing it all in a country with a new language and culture is not a recipe for harmony.

I know that my spontaneity, sense of adventure, confidence, and love of change can be scary and downright annoying for someone whose natural need to think things through, check things out, and retain a sense of skepticism and pessimism can drive me from eye rolling to distraction.

We started our lives together as kids, believing ourselves to be quite grown up, unformed but quite sure of our opinions about and view of the world. Life is a better argument for Darwinism than the finch in the Galapagos. It molds us as we make many seemingly inconsequential decisions (as well as the obvious big ones, of course) and we evolve without realizing just how much until a trigger has us looking back at the journey as Amor Towles triggered me.

It’s satisfying for me, having gone on this journey, to realize that it’s been a good journey so far.

Sure, I would change some of my decisions and behaviors if I had it to do over again, but I also forgive myself because I remember where I started, who I was, and who I’ve become. I couldn’t have made those better decisions or behaved in those better ways before I became who I’ve become.

One very gratifying feeling is that of great appreciation of and love for my husband and partner of over fifty years. Sure, I would change some of his behaviors and decisions if someone put me in charge of such things. It’s a very good thing that no one will be doing that because I have a feeling it’s the disconsonance of our natures that makes it all work.

And, after all, he was doing yoga every morning for over a month in Rishikesh and is even beginning to be less squeamish about calling it yoga instead of exercise.

I don’t know where I’m going with this Ode to My Long Time Relationship just as I don’t know where our life together will take us from this charming old fashioned haveli lodging in Jaipur. I think I write partially out of nostalgia for a simpler time when couples more often stuck it out long enough to reap the benefits of the companionship and kindness of a Long Term Relationship. And maybe partially out of an awareness of the constantly evolving nature of love born from extended travel together.

It’s a wonderful thing and I wish it for more people even as I recognize that the Western world has been moving in the other direction.

I think this sociological evolution is the bastard child of good intentions. In my generation’s desire to change the world we went dashing down the path with little awareness of possible consequences. They’ve not all been good.

But that’s a thought for a different time and place.