There are a bunch of things that no one tells you about aging. Or maybe they tell you but it goes in one ear and out the other. Not relevant. Things that register in the way the laws of physics register – ya da ya da ya da.

As I turned 60 and even more after 65, I became aware of the physical aches and pains that go along with aging and, in my case, are the price for having jumped and danced around and, taking advice from The Eagles, taken my body to the limits for decades. I remember an orthopedist once telling me to keep teaching hip hop, hiking, and doing whatever I loved because ultimately even sedentary people have joint aches and pains…but they have a lot less fun getting there. I totally agree. Even on the mornings that my knees wake me up with a call for help.

It’s some of the other things about aging that I never gave much thought to (or any).

- finding conversations of people under 40 uninteresting

- having read every permutation of book and movie plots ad nauseam

- being cold (or hot) when no one else is

- losing friends to illness, lack of mobility, or death

- aging differently from significant people in my life

YIKES!!

It turns out that an inevitable part of aging is loss and grieving for those losses. Big losses and small losses. And some losses are harder than others; not necessarily the “big” ones.

We all do it differently. And it all looks different on other people.

I remember having no regrets at 50. Ha!

I remember letting go of hip hop and aerobics in the blink of an eye. Didn’t seem like fun anymore. Traded my spandex for yoga pants happily.

I remember not even entertaining the notion of a sedentary life requiring programmed exercise. Counting steps? Furthest thing from my mind.

I remember a time when illness and death weren’t even a tiny part of my thoughts.

I’d read about (other, much older) people complaining that many of their friends had fallen by the wayside one way or the other. I’d heard them extolling the virtues of cultivating younger friends to combat loneliness. Scroll up – in one ear and out the other.

My partner “lost” his mother 10 days ago. My mother-in-law died. She wasn’t a nice person. Not a good mother. A narcissist. She was lively and charismatic and loved to be the center of attraction, but her children and friends paid a heavy price. She had dementia for the last five of her 93 years and didn’t recognize my partner or his sister who, in spite of a complicated and challenging relationship, made sure her last years were comfortable. If emotions were rational, no one would mourn her death. But if emotions were rational they wouldn’t be called emotions.

emotion – derived from the Latin term emovere;

to agitate or stir up. The affective aspect of consciousness

My parents are both long gone. My father died thirty years ago and my mother about twenty. Fortunately for me, I made my peace with both of them while they were alive. They weren’t partners in the process, but the possibility of relating to them with equanimity in life was a blessing.

My partner wasn’t so fortunate.

Watching his mourning process has been thought-provoking and, yes, emotional. A loss of innocence. A loss of possibility. A loss of the luxury of avoidance. A recognition of the loss of reconciliation. A loss of the comforting delusion of immortality.

My mother had bi-polar disorder. The shadow of her disease lurked everywhere. Sometimes it blotted out all joy and normalcy; sometimes it was a vague and disquieting sadness in our house. It was always a sense of waiting for the other shoe to fall. I was entrusted with her care from a very young age. I gained confidence and self-esteem that’s served me well throughout my life. I also harbored resentment and fear of chaos in the world.

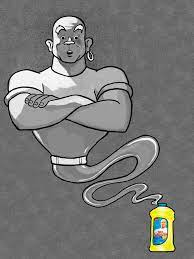

I used to imagine myself a very small figure, wrapping my arms around my knees, head bowed, before a huge Mr. Clean-type genie, rising out of a magic Aladdin’s lamp, arms folded, scowling down on me. I didn’t understand the image or why it recurred so consistently and persistently throughout my life.

The image vanished, never to return again, once I worked through my relationship with my mother. It was a loss I recognized with gratitude. I forgave my mother, without her permission, and realized one day that I felt a loving, empathetic sadness for her; a brilliant woman whose life was taken from her by a crippling disease no one understood at the time. A tragic loss. No second chances.

Not so with my mother-in-law.

The frightening image my partner has of her is his to tell, not mine, but he has one no less frightening than mine.

It’s difficult to accept that a person can be unkind, cruel, and totally lacking in compassion. How much more so when it’s your parent; the person entrusted with your care, emotional and physical? It’s tempting – no, imperative – to search for an underlying reason to shed a more sympathetic light on such a parent.

He searched. We searched. The round of reasons we tried to fit into the square peg bulged and defied imagination.

Ultimately, the physical loss of his mother grew into the loss of innocence. The first kind of loss is met with a simple grief. She was, after all, turning 93 two weeks later and hadn’t been herself for years. The second kind of loss is far deeper and creates a grief that is painful at any age, but magnified at 70, after so many years of pretending, ignoring, excusing, and hoping.

Two of our sons were at their grandmother’s funeral to support my partner and express their respect for family ties. When I talked to our older son before he left to meet us at the airport, he asked how his father was doing. I explained that he had many unresolved issues with his mother and now they’d never be resolved. I added how important it is to confront unfinished business with a parent in life. Hint, hint. (He moved on.)

There’s a lot of loss involved in aging. Loss of a parent. Loss of freedom from pain. Loss of mobility. Loss of long term friends. Loss of mental acuity. Loss of hearing. (Shall I go on?)

A Buddhist parable addresses the problem of suffering. It describes the two arrows in every difficult situation in life. The first is the arrow of pain, in this case loss, and the second is the arrow of suffering. The first is inevitable but the second is optional. It’s the arrow we shoot into our own hearts with our reaction to the inevitable losses that come with aging.

So many circumstances are beyond our control. My mother’s disease; my mother-in-law’s nature.

We can only prepare ourselves by nurturing our souls. By taking a deep dive into ourselves and becoming familiar with the particles of a higher power which exist inside each of us. By honing our ear to hear the pure voice of equanimity which resides there.

Many years ago I weighed the option of starting a hospice center. I had a conversation with the man who created a small hospice center in Jerusalem. At the time he was in his early 80’s. He exuded empathy and kindness. We spoke after I took a tour of the center with a staff member. I was surprised to see that each of the rooms had two residents. I asked the founder of the center if it was disturbing for the residents to witness the death of their roommate. His answer equally surprised me. He said that with the work done with the residents, every death since the center’s inception had been peaceful, and inspired serenity in those who witnessed it.

Choosing equanimity isn’t a one shot deal, and it’s not easy. It takes diligence and practice and work. Committing ourselves to the effort doesn’t ensure total success, or success every time. But to quote a poet by whom many of our lives have been enriched, Mary Oliver,

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

So agree with everything. Love the arrow parable.

Beautifully written … and taken to heart. And I’m sorry for the loss of your mother-in-law, and your mother, and all the other losses. Now I see why you’ve become such an avid Buddhist.