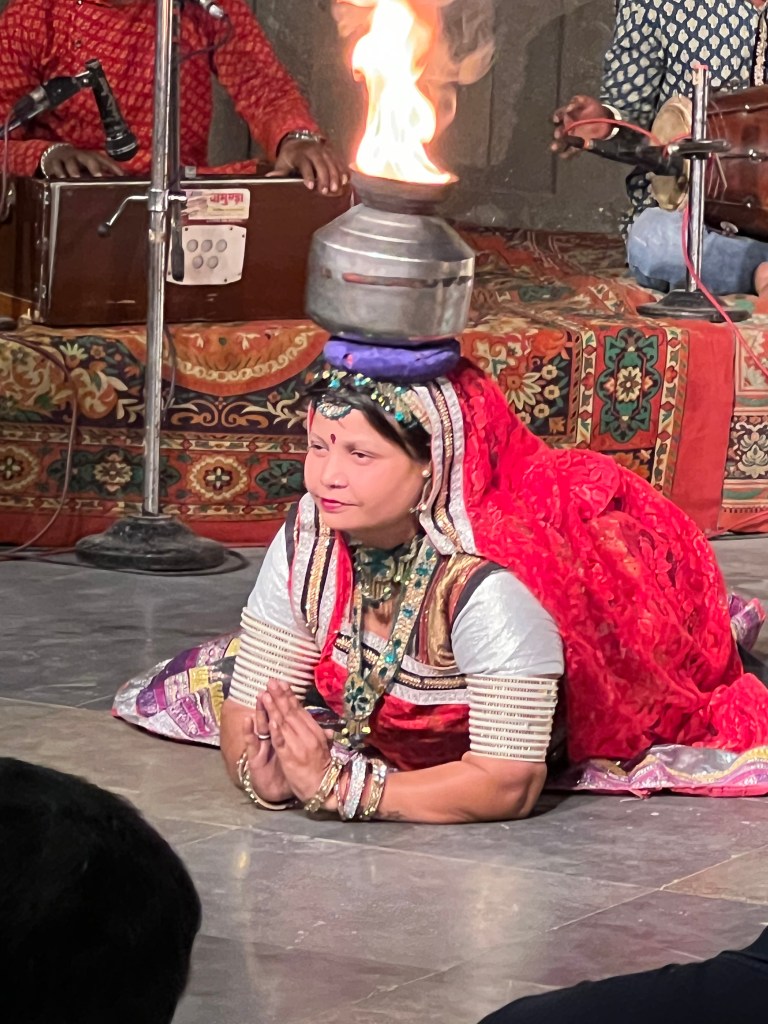

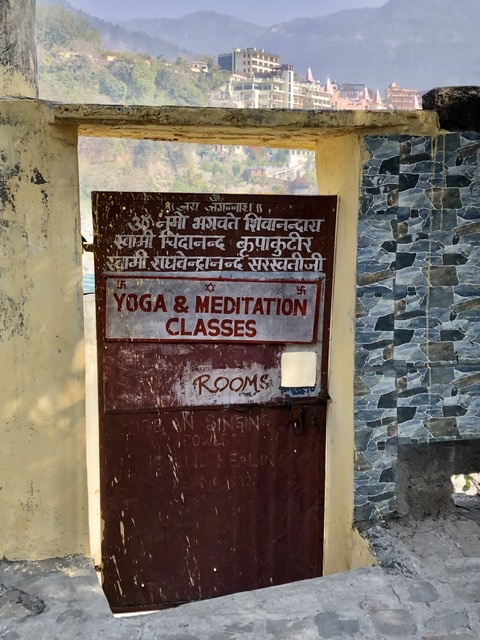

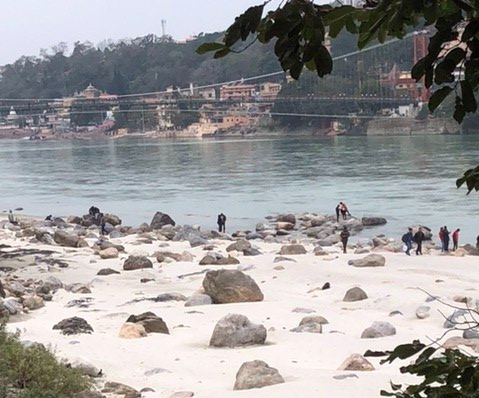

All told, we’ve been in India almost a year. We’ve spent over two months in Kerala, four months in Rishikesh, and a week to ten days in Hampi, Meysore, Delhi, Goa, Mumbai, Varanasi, Darjeeling, Khajuraho yogashram, Kaziranga, Puri, Shimla, Dharamshala, Dalhousie, Chennai, Pondicherry, Auroville, Bandhavgargh, Rambagh, Jim Corbett, and the Andaman Islands.

My partner has been learning Hindi off and on for 7 years. Between his Hindi and Google audio translate we’ve had many conversations with people about their lives and their opinions about many issues – geopolitical, philosophical, sociological, religious, and how they view the future.

We’ve observed familial interactions, public and less public behaviors, hygiene and eating habits, changing clothing preferences, and acceptable and less acceptable commercial activities.

We’ve experienced the kindness, patience, and acceptance of Indians in many different situations from driving to waiting in line to communication difficulties to cultural misunderstandings.

When asked how many children an Indian has they will invariably give a number that reflects only male children. Mothers as well as fathers respond in this way. Sexist? I don’t think so. It seems that in traditional Indian families (and in spite of rapid and visible change it’s estimated that over 90% of Indian marriages are still arranged marriages) sons remain in the nuclear family home after they marry. Their wives become subservient to the matriarch who travels with them on vacations and sets the tone for parenting. Daughters move on to their spouse’s family. They are only temporarily part of their parents’ lives. I’ve come to believe that is why they’re not included in the natural spontaneous reply about the number of children in the nuclear family.

Is this belief accurate? Maybe. Maybe not. One thing I’ve learned is there’s no point in asking for clarification. Such requests are met with puzzled expressions followed by acceptance of my theory regardless of its accuracy or inaccuracy.

Here’s a much more prosaic, but much more day to day question I’ve been asking in vague euphemistic terminology since our very first visit in 2016. Why don’t Indians, especially women, use toilet paper? It’s excellent for the ecology of every country and certainly one with a billion and a half people, and yet… What’s the deal? It’s all well and good that our tushes and other intimate places are actually cleaner after that spritz from the bidet but what is it about walking around wet that doesn’t annoy them? And is it even hygienic?

They’ve learned that foreigners need toilet paper. Hotels provide small rolls of it and are happy to replenish it as frequently as their patrons allow themselves to make the request (we tend to buy our own to avoid the issue altogether). But when asked why they don’t require it themselves I’ve been met with puzzled expressions and literally no answers, They don’t understand why I do require it but accept it and I don’t understand why they don’t require it but still ask from time to time.

The nearest things I’ve received to an answer have been (1) the concept of the comfort of dry being preferable over damp is a Western concept (really?!?) and (2) you can carry a small towel to dry off, keep it in a small plastic bag all day and wash it in the evening (a nice solutionbut I doubt Indian women actually do that).

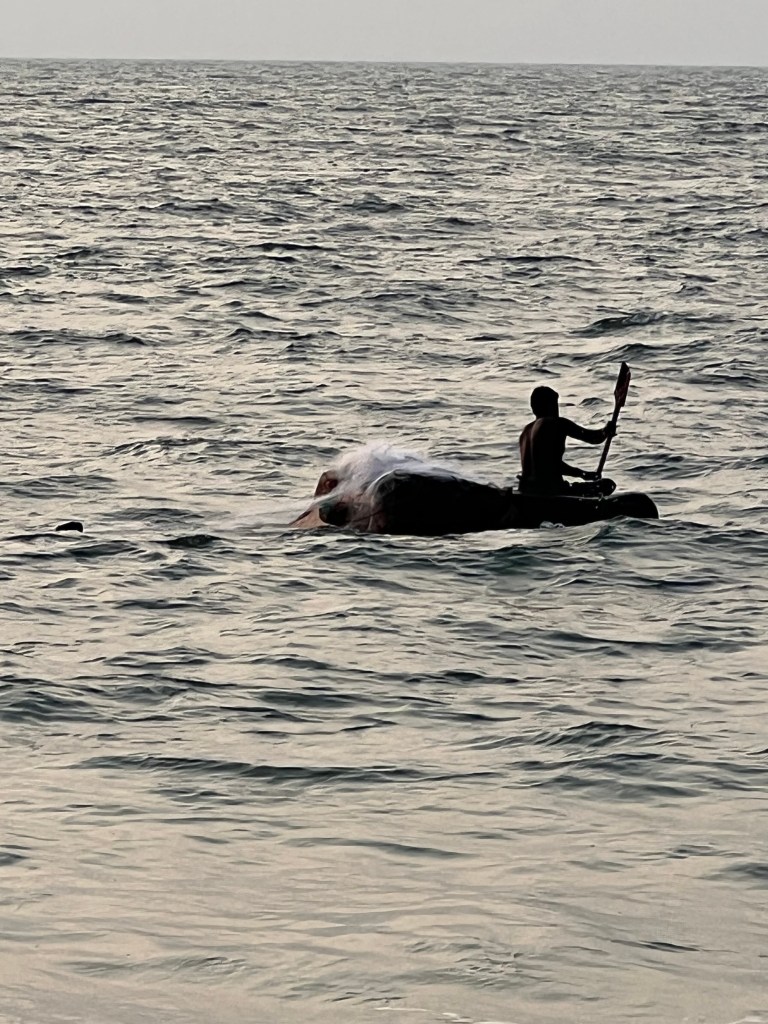

That may be similar to something an Indian friend of ours said recently. He owns an amazing guesthouse literally 50 meters from a pristine Arabian Sea beach. He’s made lots of improvements over the past few years. Indian tourists are accustomed to ordering their meals and eating in their rooms. They seem to prefer it. It might be a question of the chicken and the egg. Maybe at one time hotels didn’t have restaurants. So our friend didn’t have a restaurant but realized that the (mostly foreign) guests preferred not to eat in their rooms so he added a really nice place to eat.

His showers had no hot water. Granted it’s quite hot in Thumboly Beach and the locals see no need for hot water but others do. As a result, he decided to arrange hot water and told us he had done so. In most Indian showers there’s a shower head and also a faucet beneath it about a foot annd an half off the floor with a bucket and plastic cup below it. Turns out he set up water in the lower faucet and not in the shower head.

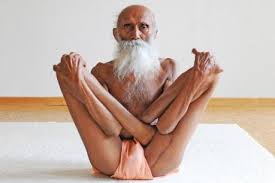

When we laughed about it with him he said something quite true and profound. He said that one of the differences between Israelis and Indians is that Israelis look at something and immediately start figuring out ways to improve upon it while Indians look at the same thing, accept it as is, and immediately figure out a way to live with it. There are pluses and minuses in both approaches.

And what about respect for personal space, acceptable noise levels in public places or in hotels late at night, what it means to be a couple, the relative merit of avoidance or honesty in confronting legitimate disagreement or misunderstanding; the cultural differences go in and on.

Even when we think we get it we have to keep asking ourselves if we really get it.

There’s no escaping the fact that part of the joy in being in India is the adventure of the Western shrug of shoulders or the Indian wag of the head. The humor in “I don’t know.” The puzzled expression followed by a smile.

You aren’t in Kansas anymore, Dorothy. And ain’t that grand?